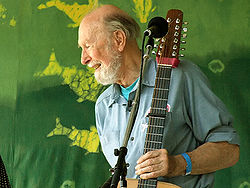

Pete Seeger obituary: Musician and activist dies aged 94

The poet Carl Sandburg once paid tribute to Pete Seeger by describing him as “America’s tuning fork”. As a musician, songwriter, teacher, environmentalist and political activist, Seeger served as his country’s moral conscience, often doing so in the face of hostility and blacklisting. He remained, nevertheless, a principled, dignified and, above all, humane figure.

“My basic philosophy in life,” he once said, “is that I’m a teacher trying to teach people to participate, whether it’s banjos or guitars or politics.” And teach he did, showing generations of Americans how to sing and make their own music.

He was a formative influence on succeeding generations of folk-oriented performers – “Most of us,” Joan Baez once said, “owe our careers to Pete” – and many of his songs have become standards, among them “If I Had a Hammer”, “Turn, Turn, Turn”, “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?”, and he popularised the anthemic “We Shall Overcome”. He was, in the words of former President Clinton, “An inconvenient artist who dared to sing things as he saw them.”

Born in 1919 Seeger was exposed to both music and political activism from an early age. His musicologist father Charles had been Professor of Music at the University of California, Berkeley until his pacifism during the Great War saw him hounded from his job, while his mother, Constance Edson Seeger, had been a successful concert violinist. While in his teens he discovered the musical sound world that was to occupy him for the rest of his life.

“In 1935 I was 16 years old, playing tenor banjo in the school jazz band,” he recalled. “I was uninterested in the classical music which my parents taught at Juilliard. That summer I visited a square dance festival in Asheville, North Carolina, and fell in love with the old-fashioned five-string banjo, rippling out a rhythm to one fascinating song after another. I liked the rhythms. I liked the melodies, time tested by generations of singers. Above all, I liked the words.”

In time the lure of folk music would prove too great to resist and, having gained a place at Harvard, Seeger gave it up to explore the highways and byways of America. En route he worked alongside Alan Lomax at the Archive of American Folk Song and met the veteran musicians Leadbelly and Aunt Molly Jackson. In time he found himself performing at rallies for the Dairy Farmers Union-organised New York Milk Strike, an experience that heralded a commitment to social activism that would endure until his death.

By 1941 he was organising the Almanac Singers, a group of like-minded musicians, including Lee Hays and Millard Lampell, whose repertoire of anti-fascist and pro-union songs and folk tunes gained exposure through weekly Hootenannies on national radio. Woody Guthrie was a sometime member of the Almanacs and, in time, became Seeger’s mentor.

“I learned so many things from Woody that I can hardly count them,” Guthrie said. “The way he could identify with the ordinary man and woman, speak their language without using the fancy words; his fearlessness, his readiness to dive into any situation no matter what it was, and just try it out.”

Drafted into the army in 1942, the same year in which he joined the Communist Party, he performed for fellow soldiers and continued to collect songs. On being discharged in 1945, he and his friend Lee Hays developed People’s Songs Inc., an unsuccessful marriage of music and trade unionism.

In 1948 he formed the legendary Weavers with Hays, Ronnie Gilbert and Fred Hellerman. In retrospect the quartet seem not to have found the saccharine orchestral arrangements on popular hits such as “Tzena Tzena” and the multi-million-selling “Good Night Irene” (both 1950), and “On Top of Old Smoky” (1952) quite to their taste. They did, however, serve as a primary catalyst in the folk revival and, besides, the political paranoia that walked hand-in-hand with the ascent of McCarthyism eventually got the better of them and they found themselves banned from most broadcast outlets.

In 1955 Seeger was called before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. When asked about his political associations he replied: “I am not going to answer any questions as to my associations, my philosophical or religious beliefs, or my political beliefs … or any of these private matters. I think these are very improper questions for any American to be asked, especially under such compulsion as this.” His disinclination to respond saw him sentenced to a year in prison for contempt of court and, although he served only four days, the blacklisting that followed saw him absent from television and radio for some 17 years.

In the 1960s he played a major role in the folk revival, recording prolifically for Folkways and Columbia and watching as both Peter, Paul and Mary’s cover of “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” (inspired, in part, by a passage from Mikhail Sholokhov’s And Quiet Flows the Don) and the Byrds’ version of “Turn, Turn, Turn”, with its lyric taken from the Book of Ecclesiastes, entered the upper echelons of the pop charts. In time, “Flowers” became popularly associated with Marlene Dietrich who recorded it in English, French and German; it remains one of the great political songs of the 20th century.

Seeger was a co-founder of the famed Newport Folk Festival; his reported sense of betrayal when Bob Dylan “went electric” at the 1965 Festival has been greatly exaggerated. He felt, simply, that Dylan’s voice was being drowned out. “I couldn’t understand the words,” he recalled. “I wanted to hear the words. It was a great song, ‘Maggie’s Farm’, and the sound was distorted. I ran over to the guy at the controls and shouted, ‘Fix the sound so you can hear the words.’ He hollered back, ‘This is the way they want it.’ I said ‘Damn it, if I had an axe, I’d cut the cable right now.’”

He further antagonised his political enemies by supporting the civil rights movement and actively opposed his country’s involvement in the Vietnam conflict, writing the memorable “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy” (1965) in response to a picture of American troops wading across the Mekong River. He also became interested in environmental causes, fronting a campaign to clean up the Hudson River and, in 1969, forming an advocacy group, the Clearwater Organisation, to protect it in the future.

In the decades that followed Seeger’s position as a treasure of American music was firmly cemented. In 1993 he was honoured with a Lifetime Achievement Grammy and in 1994 became the recipient of both the Presidential Medal of the Arts and a Kennedy Center Award. He was inducted into the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame in 1996 and in 1997 received another Grammy Award when his album Pete was named Best Traditional Folk Album. In 2006, his friend Bruce Springsteen released a well-received tribute album, We Shall Overcome, the Seeger Sessions, which featured folk songs popularised by Seeger; it won the Grammy for Best Traditional Folk Album the following Spring. In October 2011 Seeger again found himself in the news when he and Woody Guthrie’s son, Arlo, led a march through New York in support of the Occupy Wall Street movement.

He remained philosophical about his success to the end, commenting: “Life has been easier on me than any lazy person like myself has the right to expect.”

Source: The Independent